DŽENTRIFIKACIJA SAVAMALE ili GONJENJE SLONOVA

/ Boris Novachi Bojic

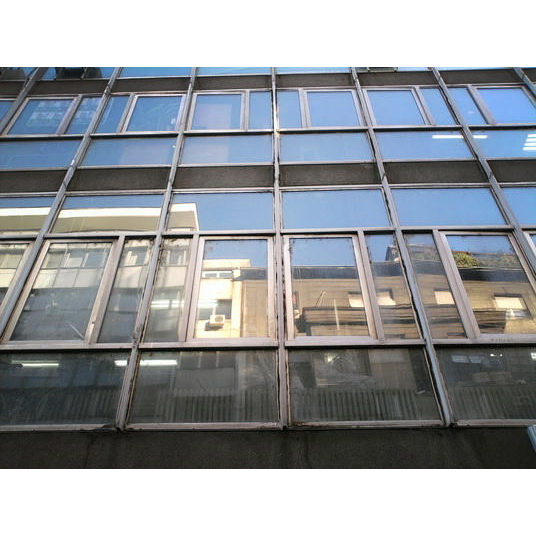

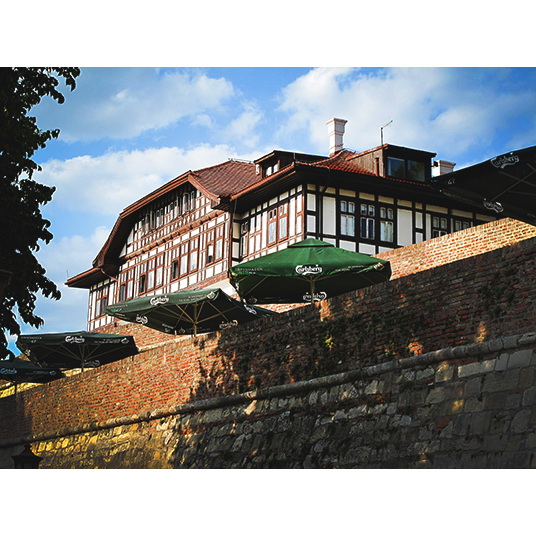

Građevinski prestupi po centru Beograda, presvučeni i pakovani u staklene rastere, verovatno referišući na modernost, čija se geometrija tokom godina, uz pomake u tehnologiji i uz slavlje, polako oslobađa pravouglih tvrdnji, dobijajući i vijugave elemente, svedoče, ali ne pripovedaju.

Da li je to možda neka vanvremenska arhitektonska igra proporcijama koju neškolovano oko ne može da razume, nešto poput radova Bauhausa, ili su to možda nekakvi konstruktivistički citati? Ne, to su ekonomski objekti koji mogu da stoje bilo gde i nemaju nikakav vizuelni raison d'être.

I dok se nadamo da je ta moda prošla, da naše oko možda neće morati da gleda nova svedočenja profiterske nesavesnosti, niče sledeće, koje ćemo, kao i sva prethodna, morati doživotno da gledamo, tešeći se još sećanjima na grad - kao uži centar. Ili kao grad uopšte, grad koji je uistinu imao previše napuklina, ali je njegova arhitektura, iako možda često u svom hronološkom dijapazonu oštećena i puna prekida, bila posve autentična. Inače sad već opšte popularnog, a eklatantno populističkog objašnjenja rasterizovanih staklenih fasada, kojeg se neko jednog dana bio dosetio, kako one ne remete urbani pejsaž, jer verno reflektuju susedna istorijska zdanja, latiće se danas svaki nedomišljati arhitekta, tj. njegovi siroti prostituirajući praktikanti za još jedan red u svojim CV-jima, sa njegovim potpisom u podnožju projekta. Laik bi poželeo da to sve bolje shvati, pa bi možda pitao: "Šta će nam reflektovani Konj ili jedna reflektovana Terazijska česma u naspramnoj fasadi?", ili: "U šta ćemo uskoro gledati, kada staklo bude reflektovalo staklo?"

Zakoni o zaštiti istorijski relevantnih objekata u Beogradu čine se kao nekakvi federi; tu su da neminovno rušenje starog, zbog opasnosti od obrušavanja, tek malo priguše, kako nam ga ne bi bilo mnogo žao usled silne dramatike padanja fasadne ornamentike na trotoar.

"Sve novo" je puls vremena, ili novi "novi romantizam"; neka bude i loše, samo da nije staro. Ako mora da bude staro, onda kao neutilitarni suvenir. To nam obezbeđuje distancu od samih sebe; zadržan i revitalizovan deo spoljne ljuske sa novom namenom, gde ničeovsko „lažno je vrednije od pravog“ perfektno nalazi primenu; nešto poput filmskog seta – banalno inscenirana, kultivisana, afektirana i često nevešto podražavana starina. Beograd postaje mesto nemilične i nesistematske ekskavacije autentičnog, poput uklanjanja bolesnog i nekrotičnog tkiva.

Mi, Beograđani, kao ni žitelji bilo kojeg drugog grada, nikada nećemo postati građani sveta tek živeći u urbanoj sredini, ne zato što to ovo ili neko drugo podneblje ne omogućava, nego zato što taj izraz ne funkcioniše kao plural. Pojedinac, doduše, to sigurno može postati. Ali, neka ne zavara dvonedeljni paušalni aranžman u Hong Kongu, Dubaiju ili u nekim drugim big-beng tehno-mekama. Građanin sveta se ne postaje putovanjima, niti ona mogu biti lekcije o tome kako graditi Beograd. Beograđani, kao i drugi ljudi, koji žive u gradovima, oduvek su bili mešavina raznih prolaznika i doseljenika: od trajno pubertirajućeg, nihilističkog i ciničkog vrednovanja sveta, preko palanačkog oportunizma i ksenofobije ili levantinske ritualske gostoljubivosti i želje da se bližnjem ugodi, do geocentrične pseudoaristokratije, autističnosti ili naivnog obeskorenjenog pomodarstva nalik jednodnevnim mušicama. Svi gradovi na svetu mogu da se pohvale ovakvim i sličnim miksturama, ali, kulinarski pojednostavljeno rečeno, mera je presudna i unikatna karakteristika svakog od njih.

Beograđanska mikstura 20-og veka pretrpela je mnoge smetnje, prekide i prekretnice, čija je dalja obimna geneza u mnogome dekoncentrisala i decentrisala kulturalne skice i težnje. I dok su se države sada već drevnog istočnog bloka uz vrtoglavicu i mučninu dovijale kako da, kaskajući za uzusom i habitusom zapada, sintetičkim putem plauzibilno materijalizuju pedeset godina nedostajućih kapitalističkih iskustava u svojim komunizmom opterećenim identitetima - na doboš sa autentičnošću, Beogradom, koji je tada u višegodišnjem embargu, tek koračaju policijski kordoni koji mlate izgladneli, nezadovoljan i polulud narod kao volove u kupusu, ne bi li ih naučili poniznosti u diktaturi, a usled nestašice hrane i hleba u gradu, beogradski glumci, gostujući u televizijskim emisijama, razmenjuju recepte za najjeftinije testo koje se najbolje diže i diskutuju o tome, smejući se svom jadu, da li u proju staviti i po koju kockicu slanine, kako bi sitost duže trajala.

Zadatak jednog takvog društva je, samo desetak godina kasnije, nakon takvih i mnogih drugih iskustava i stavljanja na probe, da shvati i kritički se postavi prema nadirućoj džentrifikaciji.

Mentaliteti su veliki, teški, tromi i spori.

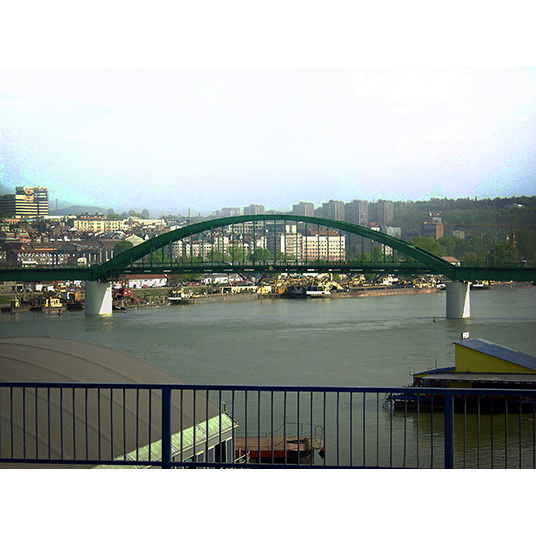

Iako kasno-, pa već i postkapitalistički produkt u prvoj deceniji 21. veka, deceniji svoje naročite ekspanzije, džentrifikacija ne nailazi na odobrenje ni sada već nešto starijih posleratnih generacija koje su rođene i rasle u kapitalističkim uređenjima zapadnih zemalja. Čak i ti ljudi žele od džentrifikacije da sačuvaju i da sami kreiraju zelene prilaze rekama u centrima gradova; ne žele skupocene dokove u hromu i tikovini; ne žele da napuste klubove kulture koje su sami osnovali i sklepali u, do još nedavno, profitno potpuno neinteresantnim i dezolatnim četvrtima, koje upravo zahvaljujući njima postižu status kultnih umetničkih četvrti - ne samo zahvaljujući njima, kao prvoj, nego sada i njihovoj deci, kao drugoj generaciji. To su četvrti gde bi svaki bohemien bourgeois soldat, radi titule dekadentnosti i svojih, usled nedostatka vremena zbog rada za nekog trgovinskog giganta, neostvarenih umetničkih afiniteta, rado živeo i bio spreman dobro da plati. Ali avaj, podovi škripe i instalacije su stare, a ulicama šetaju obično odeveni ljudi. Džentrifikacija takvima rado izlazi u susret, pod nimalo povoljnim finansijskim uslovima svojih građevinskih programa klasno-topološke getoizacije, ali je i prisiljena na kompromise nailazeći na otpor osvešćenih građana.

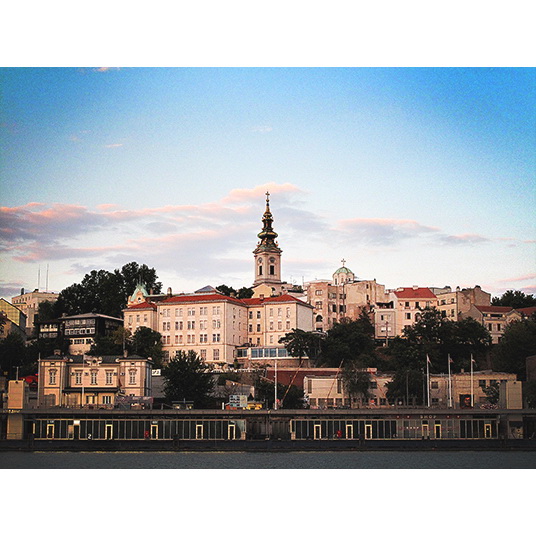

Za to vreme mi, Beograđani, tek učimo kako da se po novom međusobno pozdravljamo: da li srdačno ili pak odmereno i poslovno? Učimo da koristimo planere i kalendare; mi, koji smo do nedavno za sve uspevali da nađemo dovoljno vremena, sve dok moda nemanja vremena nije konačno došla i do nas. Džentrifikacija operiše jako površno, baš poput sveta zbog kojeg i postoji. Šteta je što ona ne nalazi mesto na obodu, nego u srcu grada i niče na ono malo istorijskog što je Beogradu nakon silnih rušenja preostalo, kao na priči koju bi Beograd posetiocu mogao o sebi još da ispriča. Njena svrha nije da Beograd učini lepšim i jedinstvenijim ili duhovitijim, nego profitabilnijim i sličnijim.

Ako Beograd može time da postane finansijski bogatiji, onda je barem nadati se da će loše dizajnirani elitistički i rasipnički monstrum džentrifikacije u svom polusvarenom ekskrementu izbaciti i po koji nusprodukt, na kojem će moći da buja umetnost i kultura kao neko buduće istorijsko dobro, ali verovatno još samo kao svima lako svarljiv i neopterećujuć tipski proizvod na metar ili na kilo, sa bar-kodom, à propos, adornovsko o kulturi kao poklopcu za đubre.

Autentičnost je nepoželjna. Ona, kao prirodna pojava je nešto neplansko i nekontrolisano, a to nije dobro. Nešto poput Las Vegasa, zapravo, poput Skoplja... To donosi novac.

Graditi jedinstveno, novo i savremeno uz respekt duha i mentaliteta grada – da. Očuvati, negovati i subvencionisati stare i retke zanatske inicijative, kao i rekonstruisati staro uz respekt istorije grada - opet, da.

U međuvremenu staklene zamenjuju limenim rasterizovanim fasadama. Objašnjenje u vezi sa njihovim estetskim prednostima nije za svačije uši.

Boris Novachi Bojic, 2014.

Tekst u štampanom izdanju objavljen je u četvrtom izdanju Kamenzind-a, magazina o arhitekturi i urbanizmu

*Please scroll down for the English version

GENTRIFICATION OF THE SAVA RIVERBANK IN DOWNTOWN BELGRADE or ELEPHANT DRIVING

The construction crimes visible in the buildings of downtown Belgrade are many. Upholstered in gridded glass facades - no doubt in an attempt to evoke modernity - their geometry is a departure from those rectangular statements so prevalent for years and, thanks to technological advances, we even see some curving lines. These buildings may be a testament of their time and yet they have no stories to tell. Are they some timeless architectural play with proportions, incomprehensible to an unschooled eye, comparable to the works of the Bauhaus movement? Or are they perhaps reminiscent of constructivism?

No such thing, they are just commercial buildings that could stand anywhere and have no visual raison d'etre. After another of these buildings is erected one hopes that the fashion has finally passed and that our eyes will no longer have to witness yet another new example of this dishonest profiteering. Sadly, soon enough, another such building rises from the ground, which, together with all the previous ones, we'll be forced to look at until the end of our lives, left to seek comfort in our memories of down-town Belgrade as it once was. Today, any architect without imagination will give you that commonplace, yet widely accepted excuse for the use of glass grid facades, an excuse someone thought of once and which everyone else has been using ever since, namely that glass facades allegedly do not interfere with the existing urban landscape because they reflect historical edifices around them.

Laymen might ask, in their quest to understand this, 'why exactly do we need the equestrian statue of Prince Mihailo or the Terazije fountain reflected in the opposite facade' or even 'what exactly will we be looking at in the future when glass facades simply start reflecting - other glass facades?' The laws regulating the protection of buildings of historical importance in Belgrade seem to act as mattress springs: they are there only to subtly dampen the impact of the destruction of what is old. If an immense drama is created over historical facade ornamentations falling down on the sidewalk, the citizens might feel less sorry about the allegedly inevitable tearing down of a building on the pretext that it presents a risk of collapse.

'Let everything be new!', this slogan reflects l'esprit du temps; it's a new-'new romanticism'. Never mind if the new building is ugly and low-quality, as long as it is not old. If something from a bygone age really must be conserved, then we'll make a purposeless souvenir of it. This should provide us with enough room to distance ourselves; a part of the outer shell is therefore preserved, revitalized and given a new purpose. Nietzsche's maxim 'the false has more value than the real' is perfectly applicable here. This vista begins to resemble a film set — predictably staged, artificial, overdramatized, in many parts just clumsy imitations of antiques.

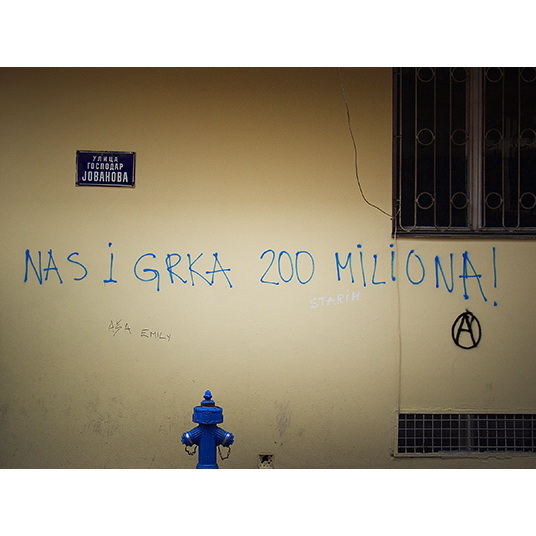

Belgrade has been transformed into a site of relentless and unsystematic eradication of everything that was authentic, as when one removes diseased and necrotic tissue from a body. Neither can we, the citizens of Belgrade, nor can residents of any other city for that matter, ever be considered citizens of the world just because we live in an urban environment. That is not because Serbia, or any other part of the world, would not like to accommodate it, but rather because the term 'citizen of the world' simply does not work as a plural. Every person has the possibility of becoming a cosmopolitan on their own. But, don't be fooled, you will not achieve it by booking a 2-week all-included tourist trip to Hong Kong, Dubai or some other big-bang techno-Mecca. One cannot become a citizen of the world just by travelling, nor can one tourist visit serve as a lesson on how to build Belgrade.

The population of Belgrade, similar to that of other cities, has always embraced a variety of passersby and newcomers with an array of different lifestyles: those perpetually procrastinating adolescence, those with a nihilist, cynical Weltanschauung, provincial opportunists, xenophobes, folk displaying a Levantine ritual hospitality and desire to please their neighbor, the geocentric pseudo-aristocrats, those just detached from the world, the naive fashion victims drawn to the style of the day like mayflies, etc. All cities in the world can boast of such similar compounds, but, put in simple cookery terms, measure is crucial to the unique flavor of each and every one.

The population of Belgrade, similar to that of other cities, has always embraced a variety of passersby and newcomers with an array of different lifestyles: those perpetually procrastinating adolescence, those with a nihilist, cynical Weltanschauung, provincial opportunists, xenophobes, folk displaying a Levantine ritual hospitality and desire to please their neighbor, the geocentric pseudo-aristocrats, those just detached from the world, the naive fashion victims drawn to the style of the day like mayflies, etc. All cities in the world can boast of such similar compounds, but, put in simple cookery terms, measure is crucial to the unique flavor of each and every one.

This unique mixture of Belgrade's has seen many disturbances, interruptions, and turning points during the 20th century. The evolution of these problems greatly disrupted and diminished cultural plans and aspirations. And while the states of the now ancient former Eastern Bloc were already vertiginously pursuing ad nauseam the mores and habits of the West, devising ever new ways to artificially yet plausibly materialize fifty years of capitalist experience missing from their communism-burdened identities — by destroying the last bits of their own authenticity, police squads were still exerting violence on the city of Belgrade over its starved, discontented and half-mad citizens, battering them like animals so as to teach them humility under a dictatorship.

As food and bread became scarce in the city due to the year-long international economic embargo imposed on Serbia, TV shows aired in which Serbian actors would share recipes on how to make the most voluminous dough with the cheapest ingredients. Laughing at their own misery, they discussed whether one should add small pieces of bacon to the corn bread in order to stay satiated for longer. Fifteen years after these and many other experiences and trials, it is imperative that this society realize what the advancement of gentrification means and to critically position itself in relation to it.

Mentalities of nations are big, heavy, sluggish and slow.

In the first decade of the 21st century, in the time of its most notable expansion, gentrification, albeit a product of the late or even post- capitalist era, was not a conscious strategy amongst the now slightly aging baby-boomer generation born and raised in the capitalist countries in the West. They too wanted to be spared from gentrification of a different sort, and simply create their own piece of green land by the river banks in their city centers. They did not dream of expensive docks made of chrome and teak, and had no intention of abandoning culture clubs they had created and built from scratch in a period when those neighborhoods were completely desolate and unprofitable.

It is thanks to them, the first generation, but also their children, being the second, that these are now reaching the status of cult artistic neighborhoods, and so, today, every bourgeois bohemian hobo, desperately trying to be seen as decadent, eager to satisfy an unfulfilled artistic affinity that had been hampered by a permanent lack of time caused by working long hours for an economic giant, gladly and readily pays a handsome amount just to settle in this kind of neighborhood.

But, alas, the floors are creaking and the installations are old, and the only people seen in the streets are dressed so plainly. Gentrification promptly meets the needs of such individuals. Under unfavorable financial conditions, its construction programs induce territorial- and class- ghettoization. Although, when it encounters resistance among enlightened citizens, gentrification, too, is forced to compromise.

Meanwhile, we, the citizens of Belgrade, are trying to learn the customs of this new era. We ask ourselves, what is the proper way to greet someone now, should I do it sincerely or in a measured, business-like form?

We are acquiring the habit of using planners and agendas, all of us who up until recently managed just fine to find enough time for everything, that is, until the fashion for being short of time finally reached Serbia as well. Gentrification operates on the surface, much like the world it exists for. And it is a pity it did not find a place somewhere in the outskirts to manifest. But no, it had to be in the heart of the city, and grow on top of the few historical sites we have, that have survived repeated destruction, and thus bury those stories Belgrade could have still shared with its visitors for some time more. The purpose of gentrification is not to render Belgrade more beautiful, unique and amusing, but to make it more profitable and recognizably similar to other cities.

If Belgrade will gain financial profit in the process, then at least we should hope that this poorly designed, elitist, money-wasting monster of gentrification would, together with its half-digested excrement, eventually spit out a couple of by-products that would encourage the flourishing of arts and culture, that would themselves become historical heritage one day. Unfortunately, it would probably just be in the form of easily digestible, light, clichéd products sold in bulk or by the measure, with an appropriate bar-code. Authenticity is undesirable.

A phenomenon of nature, it is unplanned and uncontrollable, and that is not good for the business. On the other hand, if we build something that looks like Las Vegas... or better yet, Skopje ... now that would make us some money. Building something unique, new and modern while respecting the existing spirit and mentality of the city — I'm all for it. I am also in favor of subsidizing the initiatives to preserve and foster old and rare artisan work, and to reconstruct old buildings in keeping with the city's history. In the meantime, these glass grid facades of ours are now being replaced with new, tin-made ones. As for the explanation as to the exact aesthetical advantages of one over the other, I don't think we can even stomach it.

Translated by Dina Miovic

Also published in printed 4th edition of Camenzind, the architecture and urbanism magazine, 2014